- Grammar Translation Method

- The Series Method

- The Direct Method

- The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching

- The Audiolingual Method

- Total Physical Response

The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching

Join my telegram channel for teachers.

The biggest criticism of the direct method was the lack of any educational principles to underpin it. The oral approach, or situational language teaching as it came to be known, was therefore an attempt to base a teaching approach on clear principles.

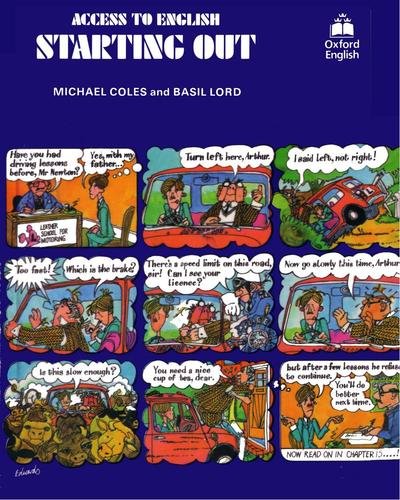

The principles for this approach were developed between the 1930s and 1960s by British linguists including A.S. Hornby, Harold Palmer and Michael West. Despite being developed some 60 years ago, this approach was nevertheless the basis of many course books in the 1970s and 1980s, and may still be in use even today in some parts of the world (Richards and Rogers, 2014). Well-known course book series which use situational language teaching include Streamline (Hartley and Viney), Access to English (Coles and Lord) and Kernel Lessons Plus (O’Neill).

Beliefs About Language

Speaking and Listening

As the name “the Oral Approach” suggests, one of the key beliefs was that speaking and listening are more important than reading and writing. As a result, language would always be presented and practised orally first, with reading and writing only coming towards the end of a lesson and only when it was felt students were ready.

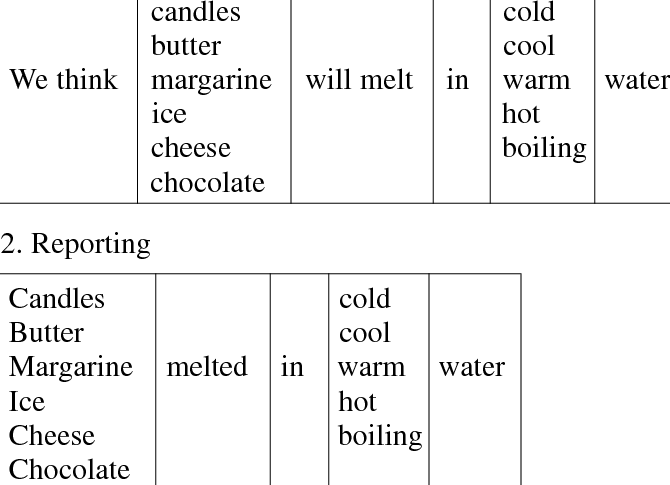

This point was to come once students had a sufficient grasp of the lexis and grammar structures. These structures, along with content words, formed the basis of a syllabus for the situational basis, being selected for their frequency, graded by complexity and organised around “situations”.

Lexis

Michael West was one proponent for focusing more on vocabulary due to his experience teaching Indian students to improve their reading proficiency. In this time, he was involved in a study noting the frequency of words across texts. This led to the publication of the Interim Report on Vocabulary Selection for the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language in 1936 and the revised 1953 a General Service List of English Words.

According to West (1954), some 2.5 to 5 million words were counted in preparing these lists. Considering that such a task would now be accomplished in seconds by a corpus, it may be difficult for some to imagine the time this would have taken back in the 1950s! The goal was to aid teachers in defining a minimum adequate vocabulary their students would need. Interestingly, West (ibid) notes that this minimum adequate vocabulary may depend upon the students’ circumstances and therefore the general service list should be viewed as no more than a guide.

Grammar

In addition to lexis, grammar was still considered necessary to be taught. Palmer (Richards & Rogers 2014) viewed grammar as the underlying patterns of conversation. This marks a deviation from the view, or perhaps unquestioned acceptance, that the grammar of speech is the same as that of written English.

Palmer, Hornby and other linguists analysed English and drew up substitution tables to help students internalise these patterns. Palmer & Redman (1969) compared these to using railway schedules to figure out your route. In their analogy, the routes more often travelled are more easily remembered and therefore no longer require the substitution tables.

Based on these substitution tables and the analysis of these patterns, the first dictionary for English students was published in 1948 (The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English).

Beliefs About Learning

Situations

As briefly mentioned above, one of the features of the situational approach is the organisation of structures into a syllabus. These were graded in order that students encounter simpler structures before more complex ones. A further important point on the syllabus however is the organisation of language into situations.

According to Richards and Rogers (2014), situation was intended here to mean the use of concrete objects, pictures, realia, gestures and actions to demonstrate meaning. In the course book Access to English (Coles & Lord, 1975) mentioned earlier, you can see the use of situations through a dialogue and series of pictures relating to it. As with the direct method then, vocabulary and structures were to be learned inductively without explanation or L1 translation. L1 was still not allowed in the classroom.

Lesson Structure

The situational or oral approach understood learning a language to be habit formation, and therefore relied upon behaviourist principles. Essentially, this involves language being received, fixed in memory and practised.

One of the common methods to practise new structures and lexis was therefore drilling, which was believed to help both memorisation and habit formation. In order for correct habits to form, it was believed errors needed to be avoided at all costs, and thus a focus on accuracy remained.

Since the main practice activity was drilling, lessons in a situational approach are largely teacher-led. Students typically listen to the teacher, repeat and may in some cases respond to commands or questions.

A typical situational lesson may therefore be organised as such:

- pronunciation

- revision of previous structures

- presentation of new structures and lexis

- drilling

- reading or writing exercises

Oral / Situational Principles

The principles of the oral approach or situational language teaching can therefore be summarised as:

- Speaking and listening were considered of primary importance.

- Building up a minimum adequate vocabulary was necessary before tackling reading and writing.

- Grammar should be based on spoken language and taught as patterns.

- New language should be sequenced by complexity and learned inductively in situations.

- Learning a language is habit formation and therefore drilling is helpful.

- L1 should not be used in lessons.

- Mistakes should be avoided at all costs.

Criticisms of Situational Language Teaching

The main criticism of situational language teaching comes from Chomsky’s refutation of structuralist and behaviourist theories of language learning. Learning a language is not simply habit formation, and this is clearly evidenced by the fact that any person can build completely novel sentences despite having never heard that sentence before.

While this is the main criticism, it is not the only criticism of situational language teaching:

- The delay of dealing with reading and writing may not suit all students. Some may need these skills more than the ability to speak or listen in the language.

- Not all language can be suitably demonstrated in clear situations. This language is likely to neglected.

- The approach requires a fluent and confident teacher.

- Teacher-centred lessons may become boring for students very quickly.

Conclusion

Established as an approach by the 1960s, situational language teaching was soon called into question by communicative language teaching. That didn’t stop it being practised until at least the beginning of the 21st Century in some contexts.

Some of the features of the situational approach have not gone away and can be seen in the PPP model that is taught on CELTA courses.

Key Takeaways

The Oral Approach or Situational Language Teaching was an approach in Britain that attempted to base language learning on principles.

Speaking and listening were considered of paramount importance. Reading and writing were considered less important.

Vocabulary took on a greater role as students tried to learn a minimum adequate vocabulary.

Grammar was taught inductively as patterns using situations.

Delivery of lessons was based on behaviourist principles which are now criticised.

References

Coles, M. & Lord, B. (1975) Access to English: Getting On. Oxford University Press.

Faucett, L., Palmer, H., Thorndike, E. & West, M. (1953). Interim Report on Vocabulary Selection for the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language. P.S. King & Son Ltd.

Hartley, B. & Viney, P. (1994). New American Streamline Departures. Oxford University Press.

Hornby, A., Cowie, A. & Windsor Lewis, J. (1948). The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English. Oxford University Press.

O’Neill, R. (1974). Kernel Lessons – Plus: Laboratory Drills and Tapescript. Longman.

Palmer, H. & Redman, H. (1969). This Language-Learning Business. Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

West, M. (1953). A General Service List of English Words. Longman.

West, M. (1954). Vocabulary Selection and the Minimum Adequate Vocabulary. ELT Journal 8(4), Summer 1954.